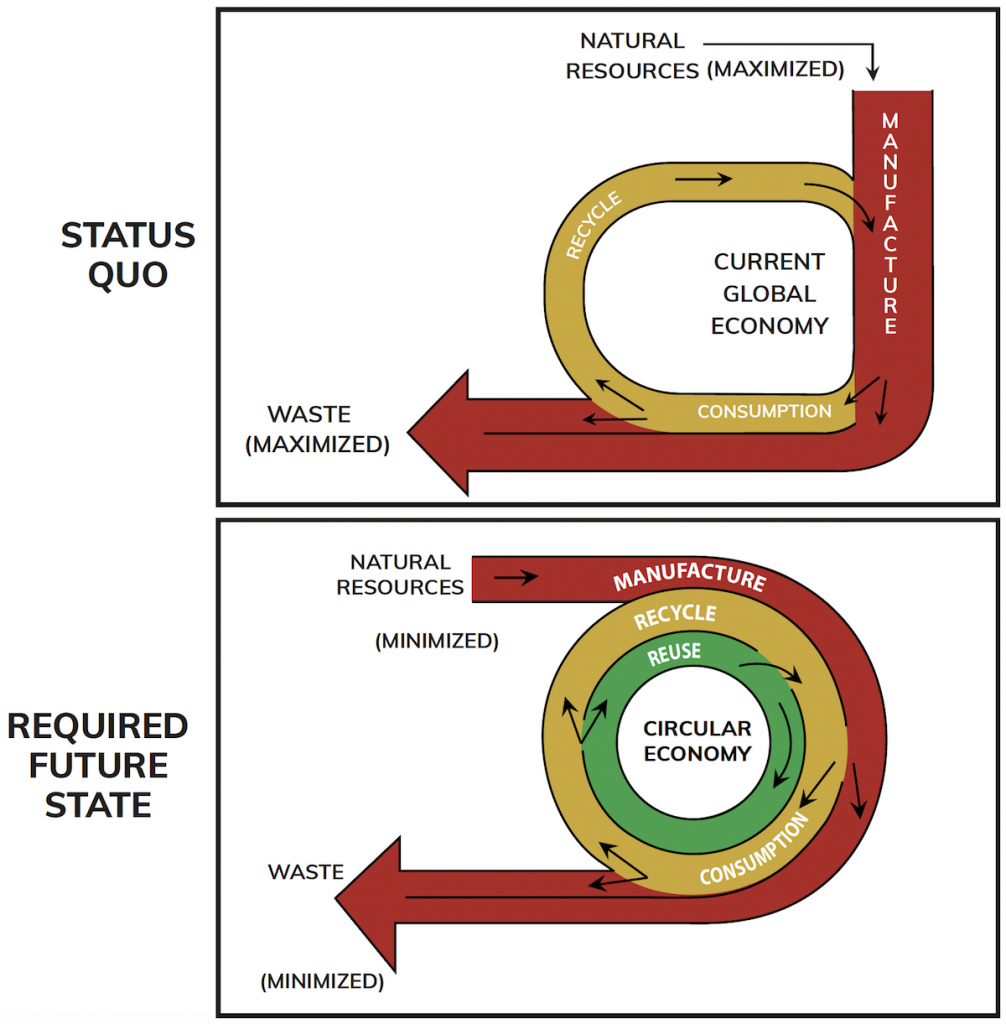

Moving towards a circular economy is central to fighting climate change. This represents risks and opportunities for the banking sector.

Defining a circular economy…

The term circular economy is widely used within the discussion around addressing climate change. It has a specific place in the detailed plans of governments, such as the EU, as they are unveiled to make global economies more sustainable. The exact definition of a circular economy varies, but the World Economic Forum (WEF) defines it as:

“A circular economy is an industrial system that is restorative or regenerative by intention and design. It replaces the end-of-life concept with restoration, shifts towards the use of renewable energy, eliminates the use of toxic chemicals, which impair reuse and return to the biosphere, and aims for the elimination of waste through the superior design of materials, products, systems, and business models.”

In simpler terms, it can be read as:

- Long term usefulness is built into product design – Products should be designed to avoid waste, which means, they should be made in such a way, that;

- They remain in use as designed

- They are repurposed

- They are recycled

- Waste is eliminated – Waste from industrial processes is often viewed as a necessary evil, but ought to be seen as a process failure. The following are to be specifically avoided;

- Landfill creation

- Oceanic pollution

- Global shipping of waste, including recycling, between jurisdictions

- Biosphere regeneration – By keeping existing goods in circulation for a longer period, it is possible to;

- Allow forests to recover and act as natural carbon sinks

- Prevent plastic in oceans from breaking down into methane and ethylene, both of which accelerate global warming

Creation of a circular economy…

The Ellen McArthur Foundation is committed to establishing a circular economy and has published a set of guidelines for policy makers to achieve that goal. Suggestions from them include:

Stimulate design for a circular economy – Product policies, building regulations, agricultural land-use, food policies, and international standards, all can accelerate the transition to ensuring that what is placed in the market is designed with a circular economy as the ultimate goal.

Manage resources to preserve value – Policies that incentivize collection, separation, and sorting systems that can support reuse, sharing, repair, and remanufacturing of products, in addition to high-quality recycling and treatment systems, such as composting and anaerobic digestion.

Make the economics work – Aligning taxation, subsidies, state aid and government funds, competition, labor and trade policies, as well as procurement, disclosure, and accounting requirements, with circular economy principles.

Invest in innovation, infrastructure, and skills – Targeted public investments in transformative business models, product, and material innovation, as well as physical and digital infrastructure, are all requirements of a circular economy.

Collaborate for system change – Establishing alignment and harmonization nationally and internationally is key, as is the development of processes that are inclusive and additive to the overall value chain, and which provide policymakers with the feedback they need.

ref: Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Universal Circular Economy Policy Goals (2021)

From the above it is clear that, for a circular economy to be established, a significant government willingness to invest, subsidize and legislate, is needed.

Governments are adopting circular economy thinking…

The EU adopted the Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP) in 2020 and it is a focal point in the bloc’s Green New Deal. Its stated aims are:

- Make sustainable products the norm in the EU.

- Empower consumers and public buyers.

- Focus on the sectors that use most resources and where the potential for circularity is high such as – electronics and ICT, batteries and vehicles, packaging, plastics, textiles, construction and buildings, food, water, and nutrients.

- Ensure less waste is generated.

- Make circularity work for people, regions, and cities.

- Lead global efforts in building a circular economy.

These aims are backed up by a 35-point initiative tracking plan that can be read here. Industries within the region can expect regulatory pressure to mount over the next few years, particularly as the EU has increased its CO2 reduction target to 55% by 2030.

The UK, following its exit from the EU, also announced a similar package, ‘The Circular Economy Package’, in 2020. The US and Canada have both been called on by the UN (speech – North America and the Circularity Transition), to lead the world in its move towards sustainability, with Phoenix and Toronto being praised for their efforts towards a circular economy. More policy is expected to come from both countries.

Financial industry needs to understand circular economics…

As is generally the case with climate change initiatives and goals, implementation is a mix of direct government action, subsidy, and regulation. The impact of the move to a circular economy will be felt by existing businesses and new projects alike, as adaptation costs and stranded assets significantly change the business projections and credit profiles of firms across all sectors. It will also create new opportunities for innovation and replacement businesses, better suited to regulatory frameworks.

Banks have to examine their own exposures and ensure that loans and credit facilities are priced for the known and expected changes to businesses they finance. At a minimum, this entails:

- Understanding current and forthcoming regulations that impact businesses they already provide credit to.

- Anticipating likely future regulations that may ‘strand’ assets and projects.

- Pricing credit to incorporate these costs and to encourage circular design.

Where policies are already published or enshrined into law, this can be seen as normal ‘due diligence’. However, for future policies, banks will have to create scenarios and associated costs to calculate the likely impacts on their balance sheets.

It is important to note that this type of credit price analysis is related, but separate to emissions reporting. Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions are useful audits of CO2 being financed, but barely touch the breadth of sustainability related impacts that a full move to a circular economy would represent. From Methane, through waste disposal, to agricultural land use, every section of the economy will be affected, and as such, banks have to be cognizant of the risks and opportunities being created.

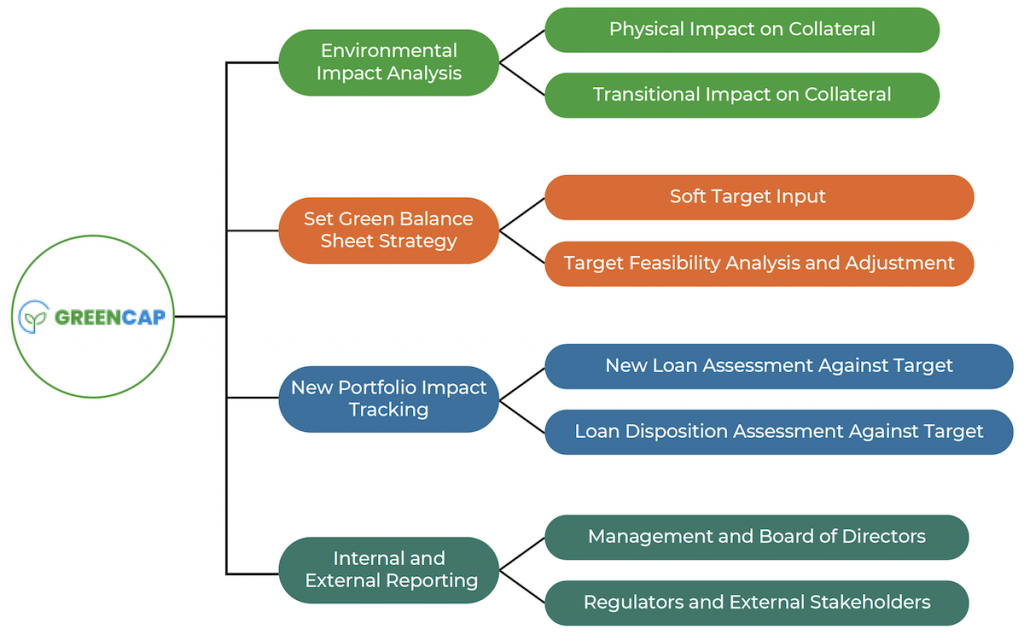

GreenCap can help…

GreenCap is a system designed to assist banks in:

- Analyzing their balance sheet from the perspective of increased risk from physical and transitional climate change.

- Creating strategies to achieve a greener balance sheet in a way that can be planned, monitored and reported.

- Work with customers to turn ‘sustainability in design’ into a direct reduction in the cost of their credit facilities.

GreenCap aims to capture the entire cost of climate change risk, and therefore, provide banks with a full picture of challenges and opportunities of the next decade and beyond.